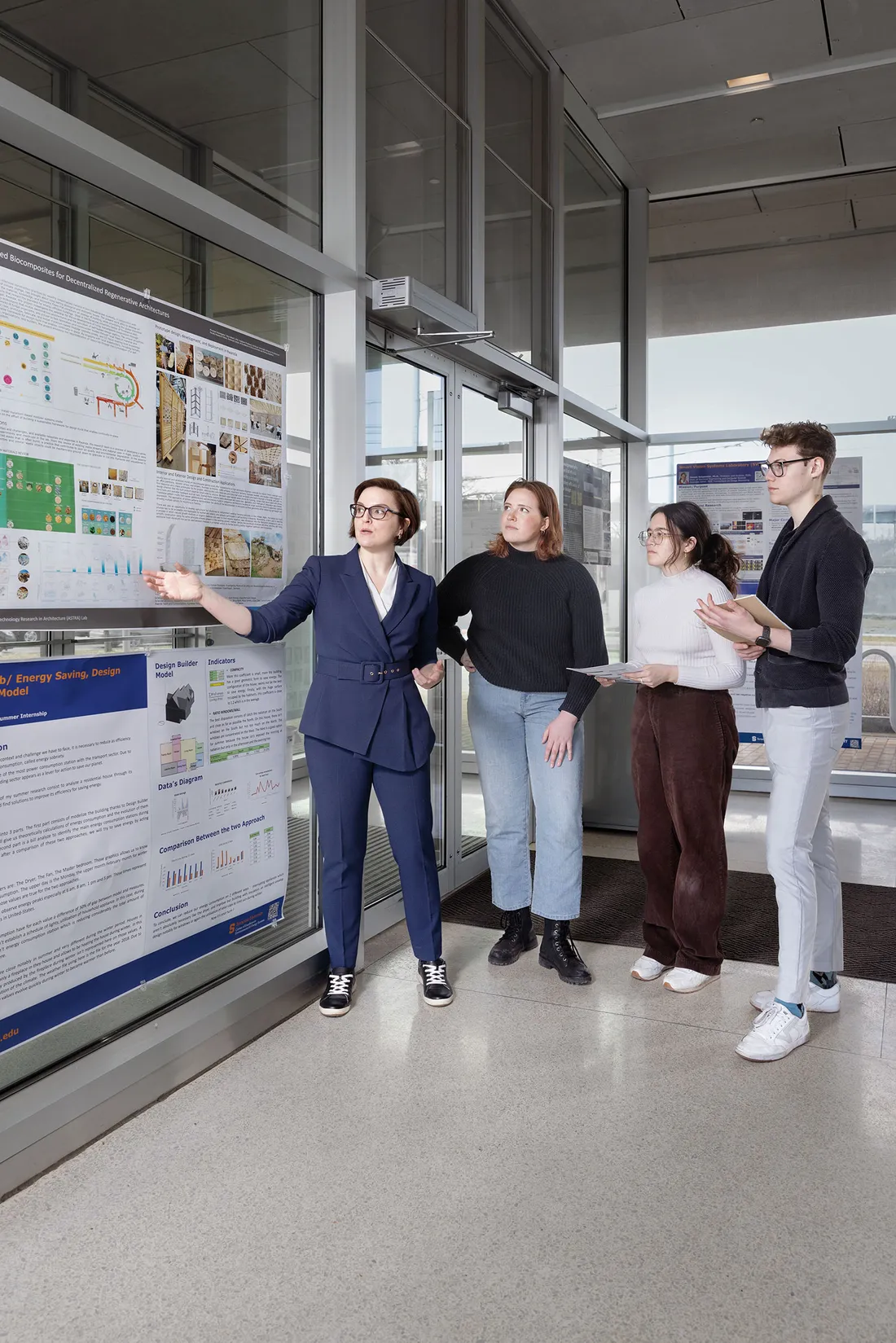

Dr. Nina Wilson, assistant professor of architecture, is flanked by Christopher Hauserman ’24 and Evelyn Broughton ’25. Both students are members of Wilson’s Net-Zero Energy Retrofit Living Lab.

Maya Angela Lagtapon Simms ’24 is among the thousands of students who, at some point during their Syracuse University careers, occupy apartment-style housing on South Campus.

“Some of the buildings are more than 50 years old and use a lot of energy for heating, cooling and running appliances and electronics,” says the senior architecture major.

Simms addresses these issues and others through her involvement with the Net-Zero Energy Retrofit Living Lab. Based on South Campus, the lab is a long-term research project exploring interdisciplinary approaches to retrofitting—the modification of existing buildings to improve energy, environmental quality and thermal comfort performance.

Led by Dr. Nina Wilson, an assistant professor in the School of Architecture, the Retrofit Living Lab is investigating two identical buildings on South Campus’ Winding Ridge Road. “The experiment is a step toward addressing climate change from the building perspective,” says Wilson, who also examines the role of renewable building materials, like mushroom mycelium, in as far-away places as Rwanda.

We recently caught up with Wilson (NW) and Simms (MS) to discuss the Retrofit Living Lab and retrofitting, in general. We were joined by fellow lab members Evelyn Broughton (EB) ’25 and Christopher Hauserman (CH) ’24, bachelor’s students of architecture; Beatriz Cypriano (BC) G’25, a master's student of architecture; and Pratik Pandey (PP) G’24, a Ph.D. student in mechanical and aerospace engineering.

The data we collect is being applied to real-life retrofitting, ultimately improving building performance while lowering energy consumption and living costs.

Beatriz Cypriano G’25

What kinds of real-world learning opportunities are available in the Net-Zero Energy Retrofit Living Lab?

NW: The lab exposes graduate and undergraduate students to fundamental research methods in sustainable building design. They get hands-on experience in performance design, energy modeling, building assessment, data analysis and prototyping in digital and physical environments.

Many students end up presenting at conferences and symposia and, in some cases, co-author trade articles. Graduate-level work is externally funded and separate from their thesis and capstone projects.

BC: I recently did 3D modeling and graphics for a retrofitting exhibition at the MOST [Milton J. Rubenstein Museum of Science and Technology]. Several of us built a large-scale model with foam, CNC [computer numerical control] machines and a 3D printer. We also created a wooden base for the model and then painted the space.

Broughton (left) is learning about the impact of low-carbon technologies on building projects.

EB: On Winding Ridge, I’ve led air quality and flow tests, interfaced with contractors and documented other activities. These experiences have helped me understand the impact of low-carbon technologies on building projects.

MS: In addition to the Retrofit Living Lab, I’ve helped Dr. Wilson develop mycelium-based composite materials. These large-scale, 3D printed structures are sustainable and biodegradable and can be used for insulation, acoustic dampening and compression. Engaging with these technologies and materials is preparing me for a career in sustainable design practices.

The Retrofit Living Lab takes a low-carbon approach to retrofitting. How do you define “net zero” and “low carbon”?

NW: Broadly speaking, carbon refers to the global warming potential of construction and demolition activities, which produce nearly 40% of all carbon emissions. [Carbon makes up carbon dioxide, which is a greenhouse gas that traps heat in Earth’s atmosphere.] Construction and demolition also account for more than 600 million tons of landfill waste a year.

A net-zero energy building harnesses as much as energy as it consumes over an annual period. It does this with renewable energy sources like solar and wind, which are coupled with energy-saving strategies, like heat pumps and a well-sealed building envelope [i.e., exterior walls, foundations, the roof, windows and doors]. This approach reduces electricity loads and building energy consumption to match what the renewables are generating.

What are other advantages of retrofitting?

“Retrofits have the potential to increase resilience in the face of climate change and extreme weather events,” says Wilson (center), an authority on building technologies research and design.

PP: A retrofitted building can perform as well as, if not better than, a new building in terms of operational use and embodied carbon. Retrofitted buildings are resilient and capable of handling extreme weather events, like heat and cold waves. They also produce three times more input energy [than output energy] and provide continuous indoor ventilation.

We specialize in deep-energy retrofits, which are more effective than conventional retrofits and can save 40%-50% of the energy used on site. In time, deep-energy retrofitting will become affordable.

NW: Our retrofitting data confirms an 80% decrease in HVAC [heating, ventilation and air conditioning] energy use, even with new cooling and ventilation systems. Apply this on a large scale, and you have less burdened electrical grids. Retrofits have the potential to increase resilience in the face of climate change and extreme weather events.

What’s the difference between retrofitting and renovating?

CH: While both involve existing buildings, retrofitting is an intentional effort to increase energy efficiency. This includes adding insulation and improving HVAC systems, which, in turn, regulate indoor air quality.

EB: Renovation focuses on aesthetics, making a building more modern looking. Retrofitting updates these systems by moving away from standards that were once commonplace—like little or no insulation, high-energy heaters and unregulated air quality—to ones that are more sustainable.

Discuss the importance of the Retrofit Living Lab.

Maya Angela Lagtapon Simms ’24 (second from right) is using the Retrofit Living Lab to prepare for a career in sustainable design practices.

BC: I see its impact on the local community. The MOST exhibition, for instance, demonstrated the importance of retrofitting—locally and statewide—in a fun, dynamic way. Kids and adults flocked to it.

I also participate in the Winding Ridge case studies. The data we collect is being applied to real-life retrofitting, ultimately improving building performance while lowering energy consumption and living costs.

CH: Our data informs long-term, low-cost solutions for multifamily dwellings. We support New York state’s Sustainability Plan, which includes a 40% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030—80% by 2050—from 1990 levels.

PP: Since joining the Retrofit Living Lab in 2021, I’ve studied door and window operation, indoor air pollutants, energy use, temperature, relative humidity and illuminance. I’ve found that retrofits lead to improvements in indoor pollution levels, building resilience, thermal comfort, energy usage and occupant behavior. By slowing climate change, we’re improving the built environment and our quality of life